by Lori Goldstein

It is the end of 2018, and despite decades of development in the field of practice, the common strategies for commissioning public art remain staid and problematic, and are often a target for critics and naysayers. These strategies expose, in many cases, outdated policies and processes, and highlight the vulnerabilities that can have negative long-term impacts on a public art program and public art’s very existence. In cities and communities nationally and internationally, the ways in which a public art project is developed and the methods for bringing the idea and concept to fruition are still rife with tension. In some instances these processes have become more convoluted, for instance a “percent for art” project triggered by capital improvements, or a grassroots project initiated by a community. It is a common occurrence that the politics of public space are exacerbated by a public artwork, especially if the work expresses opposition to the powers that control a particular site. Those politics have become even more complex as public space is increasingly privatized. Privately owned public spaces initially set aside by government and thus intended to be ”for the public” are now frequently controlled, closed-off, and monitored by corporate oversight.

Increasingly we are experiencing the critical questioning of representation in public space, as recent monument debates demonstrate. Who is being represented in public and why? Who decides for others what is represented in public space? Such necessary and evolving tensions, among many, have led some public art curators, like Ciara McKeown, to question the traditional strategies used to commission public art. The following interview illuminates some of the challenges and obstacles involved when working within the bounds of commissioning approaches that no longer respond to the contemporary context.*

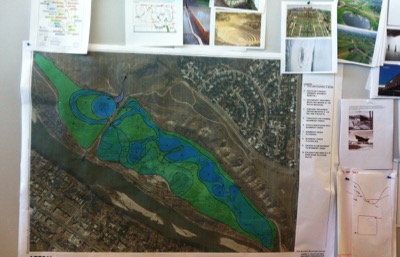

Image 1: View of East Bowmont Park. WATERSHED+ Program developed by a multidisciplinary team lead by artists Sans façon in collaboration with O2 Planning + Design and Source2Source Inc. Designed and commissioned through the City of Calgary’s UEP department with the Public Art Program (2017). Photo by Lori Goldstein.

Can you outline some of the bullet points of more traditional public art commissioning strategies? What are more common pathways to bringing public art projects to fruition?

Typically, in North America, municipal projects come from percent for art policies that are around 1% of capital civic construction projects dedicated to public art. A commission is born out from this, and often within the parameters of the capital site and restriction of funds that force the money to be spent on the site. So the public art opportunity often comes later into the development of the capital project, a roadway, a civic building, etc., and comes too late in most cases. The public art is an afterthought and is “added in” rather than “part of,” and thus begins the marginalization of the artist and the art process.

Because of where the funding comes from, many municipalities commission permanent work at this specific site through an RFP (request for proposals). How the artist works is usually quite restricted in terms of how and when they can engage with the public, how the project comes about, and what the project can be. Overall, there is not a lot of maneuvering in the process available to an artist. There is so little known about the place and the context, and so the artist is often blindly inventing a concept to place a large-scale object on the site.

In other cases, funding might come to a municipality from an annual local council-approved allotment, an annual program budget, if you will. There may be a master plan that guides the funds to projects or it is through a more community-based approach.

What are the major challenges and obstacles to creating “successful” public art projects? Have there been errors in the actual commissioning process of the work that have led to unsuccessful public art outcomes?

One of the biggest challenges has been not seeing art as an opportunity, but rather a last-minute add-on to decorate, enhance, and beautify for “placemaking.” These terms are very often used in public art calls, and we have to ask why. Art does so much more. Artists can bring so much more. Are we not doing a disservice to our cities, our publics, and ourselves by cutting off the potential before we know what it is? When working with design teams for example, artists should be seen as an asset, as bringing another perspective and asking questions others might not have thought of, rather than seeming to disrupt a power balance.

There are so many challenges, but another glaringly obvious one, in my opinion, is the lack of critical discourse in the field. There is a divide between contemporary art and public art that needs to be examined and discussed. When projects are commissioned, we need to understand them within this contemporary art context. We also need to understand projects within the site and audience context much more than we do currently. Public art should focus on relationships, on building trust and dialogue with people about place. It is a simple but powerful thing if we allow it to come about in a meaningful, open way.

Public art and contemporary art are about the world around us: responding, questioning, examining, researching. Artists bring a different perspective, and this is what we should focus on. Especially in our current political climate, seeking a new way of thinking, of considering and seeing what is around us and our place within it is paramount. When we begin with an idea or a concept or a question to initiate a commissioning process, it does not need further definition; perhaps bringing in an artist with a more fluid approach would make that process more dynamic, interesting, and beneficial for everyone. It would also be a means of looking at representation. Who makes a majority of the public art and who is represented in our public art collections have everything to do with how a commissioning process is crafted. The most successful examples I’ve seen are those that come about through commissioning models that are more open-ended, that happen through RFQ (request for qualifications), or through a lead artist and/or curatorial process.

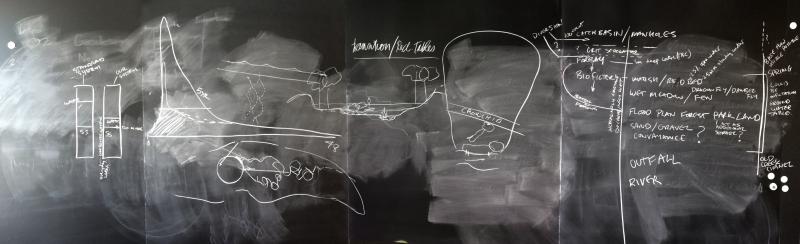

Image 2: Planning Process for East Bowmont Park. WATERSHED+ Program developed by a multidisciplinary team lead by artists Sans façon in collaboration with O2 Planning + Design and Source2Source Inc. Designed and commissioned through the City of Calgary’s UEP department with the Public Art Program (2017). Photo by Sans façon.

Do you believe that more transparent commissioning practices will lead to a more successful and well-received public art outcome?

I’m not sure I would agree with the premise that success is tied to a well-received outcome. It also depends upon what you mean by transparency: transparency where and for whom? The less mysterious the commissioning process the better, so that we are effectively telling the story about how public art happens. But I think that word “transparency” is less about a municipal or political context illuminating an economic justification, and more about dialogue. ”The public,” however, that is defined (which I always hope is expansive, inclusive and considered), is inherently part of public art, so if space is given for the artist to be part of bringing about that relationship, and if it is seen as a relationship that grows with time and dedication rather than a one-off town hall engagement event, I think we will have more meaningful experiences through public art.

What about the distinction between permanent and temporary commissions? Should they follow the same values and strategies?

I believe the focus should be on the process rather than the outcome. This distinction is useful and sometimes needed within municipal commissioning because of how the funding comes about, to define how the money will be used. However I think it’s imperative at this point in the field that we acknowledge how much of one thing we have. Many cities in North America have similar kinds of work – large-scale sculptural objects. So many examples are inspiring, beloved, and important to their place, but if we look at the whole, I think the glaring question would be what else isn’t represented in our cities and in our public art collections? I would say much of how contemporary artists are working and practicing in 2018 isn’t reflected in our public art. So it is incumbent upon us to adapt and change our commissioning structures to reflect how artists are working and how they want to work. A public space and situation is a dynamic, evolving, complex thing; what a wonderful and immensely full context to work within. Using this as an opportunity to respond would be a first value to identify, rather than thinking about what the outcome of the artwork might be. Embracing uncertainty and defending the space for the artist to more freely navigate within our public art programs is fundamental to redefining success.

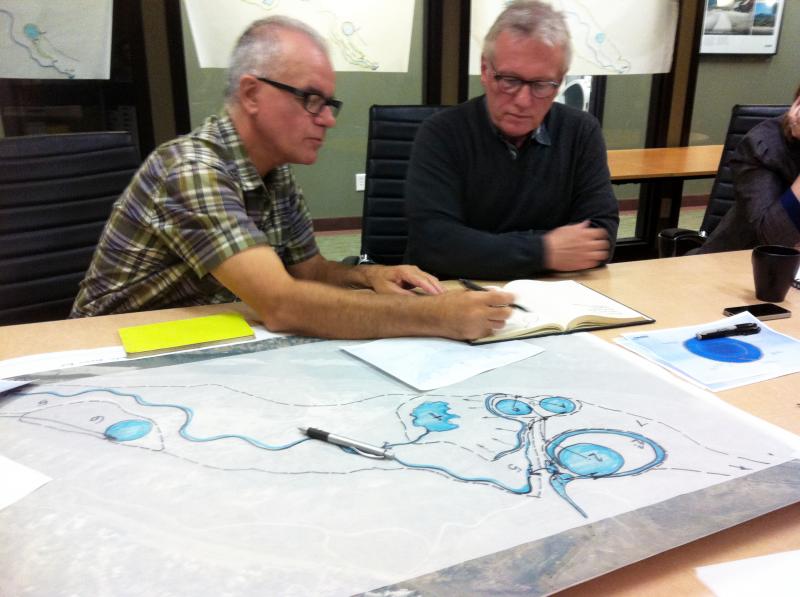

Image 3: Planning Process for East Bowmont Park featuring Doug Olson (CEO of O2 Planning + Design) and Bernie Amell (Co-owner and Senior Environmental Designer with Source2Source Inc). WATERSHED+ Program developed by a multidisciplinary team lead by artists Sans façon in collaboration with O2 Planning + Design and Source2Source Inc. Designed and commissioned through the City of Calgary’s UEP department with the Public Art Program (2017). Photo by Sans façon.

In many cases when we talk about overhauling commissioning practices or tweaking public art policy, public art collaborators wince in fear that changes to anything existing will make the entire policy vulnerable. How do you imagine approaching this conversation? Overhauls of policy or a more “flexible” reading of those policies? What approach would you take to ensure commissioning practices are in line with community values?

I believe that a strong policy is flexible, and the commissioning process need not be defined within it. A good policy leaves room for many things to happen in different ways, so I think unless our policies are restrictive the focus can be on the process, which is often where the issues or challenges are. The policy enables but should not necessarily direct the artwork, and I agree that tinkering with policy brings into question the need for it and its effectiveness at a fundamental level, which can be politically dangerous. I think the distinction between where things need to change is often within commissioning process, and not the policy – this was something we experienced in Calgary’s public art program recently.

Commissioning processes need to be updated and reflect contemporary public art practices and approaches that are successful and hold a high standard for public art. This is an important starting point because a strong vision is needed for the program and for commissioning. Community will be part of the whole program and process if we create space for that to happen through the artists, through programs, and through conversations that are about listening and sharing. For a public art program, the more the public feels they are a part of it, with a breadth of ways to achieve this, the more we can build trust and strong relationships that will support ongoing dialogue. Public art would hopefully then be seen by the public as integral to how we live and exist in our cities, towns and places, so to strengthen this will be a powerful way forward.

Image 4: Planning Process for East Bowmont Park. WATERSHED+ Program developed by a multidisciplinary team lead by artists Sans façon in collaboration with O2 Planning + Design and Source2Source Inc. Designed and commissioned through the City of Calgary’s UEP department with the Public Art Program (2017). Photo by Sans façon.

*This interview has been lightly edited.