By Megan Koza Mitchell

Los Angeles based artist Nancy Baker Cahill works at the forefront of socially minded augmented-reality (AR) art. She considers her practice to be intrinsically public, often site-specific, collaborative, and accessible, and the Los Angeles Times recently likened her work to a 21st-century version of Land Art. Her 2020 project Liberty Bell and her 2019 Battlegrounds are unapologetically political, aimed to be inclusive to as many viewers, participants, artists, and issues that their titles conjure. Both projects utilized Baker Cahill’s groundbreaking free mobile app 4th Wall as the vehicle for viewers, participants, and collaborators to house, share, and view content. However, the underlying canvas, or substrate, remains each work’s specific geolocation in public space. This article considers Battlegrounds and Liberty Bell through the lens of invisibly coded power and archaeological phenomenology, as part of the new arena of AR artwork, especially critical during a period of large-scale quarantine and isolation due to COVID-19, and a period of intense racial, civil, and social unrest that has given public voice to systemic and systematic racism and injustice that has existed for generations. Baker Cahill’s work aims to be collaborative, inclusive, subversive, and accessible to a wide range of artists and users.

Battlegrounds and Liberty Bell allow both the participating artists and the users/viewers to phenomenologically reconstruct past perception and social behavior. I would liken the use of AR as the platform for both projects by Baker Cahill to using archeological phenomenology in the landscape as a means of researching and interpreting the past and coming to a more full and complete understanding of both the physical and the social parameters of culture. Although not a new methodological approach, archeological phenomenology is only recently being utilized on a more rigorous scale, allowing scholars and researchers to take their modes of inquiry out of the computer-based Geographic Information System (GIS), which is relegated to the black box of the computer laboratory, and moving them into the physical landscape. The inclusion of augmented reality (sometimes referred to as augmented archeology) allows researchers to overlay critical data into the real landscape, along with the ability to move through both the landscape and the digital data simultaneously, creating a sense of embodiment in the physical site, thus including in any analysis and interpretation what can be felt, heard, smelled, and tasted. Archaeological phenomenology allows us to “consider the social aspects of the experience, as the space we move through is not only a construct of sensory perception, but also of social perception.”(1) In applying archaeological phenomenology to the interpretation of Battlegrounds and Liberty Bell, both the artist and the viewer act interchangeably in the interpretation and framing of a site.

If either of Baker Cahill’s projects had been conceived of as a traditional museum or gallery exhibition, one could compare the use of the gallery/museum construct to that of the GIS system, where only a rigid computational analysis of the included works could be attempted. The white box of the museum or gallery environment is rigorously controlled by the physical parameters of the location and the set of variables imposed by the curators/organizers through didactics, lighting, size of exhibition space, etc. When the artworks are taken out of a controlled environment and put into the physical landscape using AR technology, suddenly these variables can be controlled and manipulated, not only by the artist, curator, organizer through their choice of artwork and site, but also by the viewer, as they are able to freely move through the physical space. Furthermore, moving into public space opens interpretation and experience to conditions that are unpredictable and constantly changing. What is unique about using augmented reality in the landscape as a means of curating, presenting, and experiencing art, is that, through both the artist's own unique choice of artworks and site, and the viewer's interaction with the sites, AR exhibitions such as Battlegrounds and Liberty Bell can rectify misconceptions of the past, posit new arguments concerning the future, and bring issues to light in an equal and democratic playing field.

Launched in the fall of 2019, before the COVID-19 pandemic, Battlegrounds is site specific, identifying contested public sites in New Orleans, Louisiana, such as areas of land loss, Confederate statues (both existing and now empty former sites), gentrified neighborhoods, levees, prisons, blighted neighborhoods, and indigenous territories. Created in collaboration with Jesse Damiani and several local artists whose work directly addresses themes related to the sites they chose to geo-locate their work, each artist’s work can be accessed on site via Baker Cahill’s free 4th Wall app but are invisible to the naked eye. For Baker Cahill, this new subversive public art which asks no permission prompts thoughtful discourse around the most urgent issues the artworks and chosen sites represent for the communities they serve. In total, Battlegrounds is a city-wide exhibition in augmented reality activated simultaneously and experienced through smartphones.

Battlegrounds brought together an incredibly diverse group of twenty-four local New Orleans artists, all at varying points in their careers and their methodologies, to place thirty works of art in AR at various sites throughout New Orleans and some further out in the Parish. The goal was for artists to choose locations that all needed critical attention for various reasons, contested sites. These included polluted waterways, sites of confederate statues, gentrified or neglected neighborhoods, sites of the historical slave trade, prisons, and many more. Once the sites were chosen, the artists then worked with Baker Cahill to geo-locate the work they felt best responded to the site in the 4th Wall app. At the end of October 2019, these AR-sited works went live simultaneously, becoming accessible to the public free of charge through the application. Baker Cahill worked with local community arts organization L9 Center for the Arts to create a series of youth workshops using the 4th Wall app where students gained access and knowledge to AR tools and created a series of works that reflected their own contested sites within New Orleans. This resulted in one of, if not the, largest AR exhibitions attempted to date, that asked permission of no one, needed no permits, and helped expand the discourse around some of the most critical issues that the combined artworks and sites represented to the broader community served and, by extension, the global community.

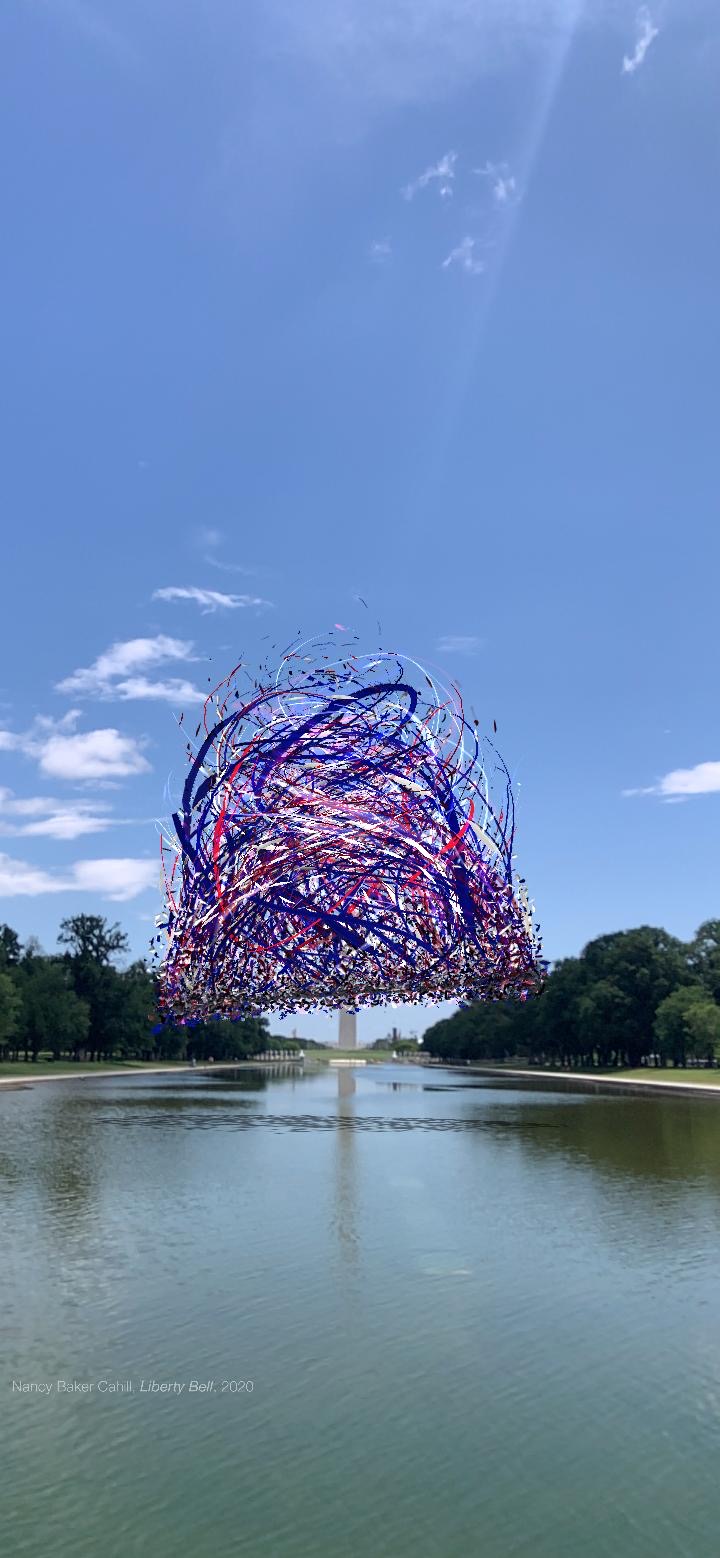

Although the subtexts are similar to Battlegrounds, for Liberty Bell (2020), Baker Cahill utilized a singular energetic red, white, and blue, bell-shaped cyclone-like drawing of her own, geo-located in six historical sites east of the Mississippi River, where history continues to be interpreted and current ideas of civil and human rights continue to be questioned. Unveiled on July 4, 2020 on the National Mall in Washington D.C., Liberty Bell cast AR shadows into the Lincoln Memorial reflecting pool as it swayed in its digital matrix of the 4th Wall app, creating an isolated yet collective experience for participants/viewers to reconsider concepts of liberty and civil rights. At the same time that Liberty Bell became present in Washington D.C., it also could be viewed at the site of the Boston Tea Party revolt in Boston, MA; at Fort Tilden, the U.S. Army installation in Rockaway, Queens, NY; at Fort Sumter in Charleston, S.C.; on the “Rocky Steps” leading to the Philadelphia Museum of Art; and at a civil rights landmark, the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma, AL, where the brutal “Bloody Sunday” attack on demonstrators took place in 1965. The accompanying soundscape for Liberty Bell transitions from the measured rhythmic tolling of a bell to a harmonious and yet discordant ringing, the sounds a blend of analog and synthetic, pulled from a variety of historical moments and places. Like the drawing itself, according to the Association of Public Art, the bell sounds, “resemble loosely knitted threads that unravel and come together in an uncomfortable, but cohesive moment. They reflect the evolution and transformation of liberty over time into the complex reality we face today.”(2)

Battlegrounds debuted in New Orleans on the tail end of the removal of several of the city’s racist Confederate monuments, calling attention to many of those contested sites and the power structures that put and kept them in place for decades. Liberty Bell picks up that mantra now as several other states are reckoning with the history of similar racist icons and as the U.S. has undergone civil unrest and reflection around the history of systemic racism that has long been ignored. As Baker Cahill herself has stated on Twitter, “It’s time for new models and new monuments.” Battlegrounds and Liberty Bell create space for those new monuments and offer a new model for engagement. These new models are more important than ever in today’s climate - one where protesters remain fearful, not only of reprisals for speaking out, but for their own personal health as the spread of COVID-19 continues to wreak havoc across the world. Liberty Bell and Battlegrounds offer viewers/users the ability to safely engage in a work of public art, adhering to any social distancing or health and safety guidelines, while at the same time opening up a critical space for a conversation around the importance of site, public art, history, and cultural agency.

Notes

1. Eve, Stuart. “Augmenting Phenomenology: Using Augmented Reality to Aid Archaeological Phenomenology in the Landscape." Journal of Archaeological Method and Theory, vol. 19, no. 4, December 2012, 582.

2. Nancy Baker Cahill’s Liberty Bell Augmented Reality Project, https://www.associationforpublicart.org/apa-now/news/nancy-baker-cahills-liberty-bell-augmented-reality-project/