By Marisa Lerer and Jennifer K. Favorite

Art collective fierce pussy is the 2019 recipient of the Public Art Dialogue (PAD) Award for achievement in the field of public art. They spoke about their formation, their collaborative aesthetics, and LGBTQ visibility in the public sphere with PAD co-chairs Jennifer K. Favorite and Marisa Lerer. fierce pussy’s current exhibitions include arms ache avid aeon: Nancy Brooks Brody / Joy Episalla / Zoe Leonard / Carrie Yamaoka: fierce pussy amplified at Columbus College School of Art and Design’s Beeler Gallery, and their work And So Are You is now on public view at Leslie-Lohman Museum of Gay and Lesbian Art. A ceremony and reception honoring the artists will take place at Leslie-Lohman Museum of Gay and Lesbian Art on Thursday, February 14 from 5:30pm-8:00pm.*

How did you first form as a collective?

We had all been in ACT UP (AIDS Coalition To Unleash Power, in New York City) but we all knew each other before ACT UP. We put a call out on the floor of ACT UP and also to people that we knew, through other queer women, and we set a meeting, a location, and we gathered there, and made the first [list] poster on a typewriter the first night we met together.

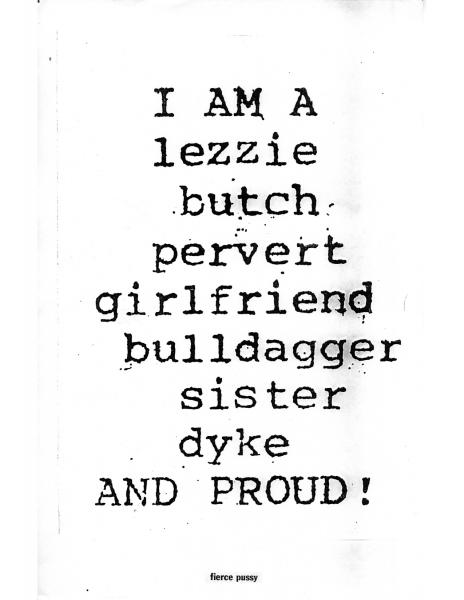

fierce pussy, “List” poster, 1991, available at http://www.fiercepussy.org/posters

The next meeting we went out wheat-pasting. It was often a changing group of people, whoever was available at any time would come. We’d target neighborhoods to go wheat-pasting in, and ideally we would know someone in a neighborhood where we could refill our water jugs and our buckets, and we’d make our wheat-paste out on the street.

Also, because of what was happening during the AIDS crisis at that time—around 1991—the immediacy of what we were dealing with on an everyday basis, with our friends who were dying or who we were taking care of, or the demonstration we were going to, fierce pussy’s response had to be quick and fast, down and dirty, low-tech and immediate.

So, certain tactics that we were learning and using in ACT UP we were also using in fierce pussy. There was a joyousness in fierce pussy that was regenerative, given the desperation of the time. Our earliest work was not about HIV/AIDS, it was about lesbian visibility and identification.

It was an activist art collective.

We really cared about and we were specific about the way the posters looked. There was an aesthetic. We used a typewriter because that was the tool we had at our disposal. The font was the typewriter font, and we liked the way that looked—it wasn’t like we had all the choices you have now on the computer. Blowing it up on a xerox machine, the noise that happened, and whether it was justified to the left, or centered—we looked at all those things, we typed them and retyped them and backspaced.

When we would go out wheat-pasting, and we would cover a wall, we would stop and look at it, “Yes, put another one there,” “No, just do one,” you know, we were working together and we were making quick yet considered decisions.

And those ways of making decisions also come because we all had our own individual art practices—that becomes part of your toolkit. Two of us were also working at magazines at Condé Nast—that’s where all the posters got run off—we would blow them up there and then run them off—Condé Nast paid for a lot of fierce pussy and ACT UP posters.

We were very young, many of us just coming out and with the AIDS activism we were doing, we were confronted with such extreme homophobia. We wanted to speak about lesbians specifically and the homophobia wielded at us, and issues of visibility and invisibility. We were talking to our community, to other like-minded people who would see the posters, and that would be a kind of shout-out to our peers. Like, “Hello—we’re here too!”

What were some of the responses to these public works you were doing?

Years later, a friend of ours, it turns out, she had a poster up in her room for years and years—we were friends forever and we had no idea she had ripped it off [of a wall] and it was up in her room. And other people would tell us, too. Helen Molesworth told us she and her mother were on the Upper East Side or West Side [at that time], and she remembers seeing our work and how much it meant to her. We didn’t sign a lot of our posters, so people didn’t know that they were made by us.

The early list posters were about reclaiming language. Taking what was derogatory and homophobic and misogynist and owning it, turning it and putting it back out, and using the power of that. For example the word “queer” was a word that was negative, used against us. So “I am a _______ and proud” was a provocative thing to be saying.

In terms of response, just to fast forward, fierce pussy worked together from about ’91-’94-ish, then we had a hiatus. In 2008 we had a retrospective at Printed Matter and we decided we would do a remix of one of the “list” posters, that we were going to bomb—that’s what we used to call it—bombing the wall—like graffiti-style bombing.

So we bombed the front of Printed Matter and then we went to lunch. And when we came back—we’d only been gone about an hour— the cops had come in because people in the neighborhood had complained about the poster that said, “I am a _______, and so are you.” They were getting all these complaints—people with their strollers were worried that their kids were going to see these words in 2008, in Chelsea. A., great, your kid in a stroller can read, and B., if your kid looked up, they would see a huge billboard —of a woman who was nude, with her legs wrapped around a Courvoisier bottle—how does your kid read that? That’s OK?

Because of the number of complaints, the cops thought it had been up for weeks, but it had only been up for an hour. We realized, “Hey, this is still so relevant, this work is still important. Words— like “amazon,” “feminist,” “pervert,” — the idea of both claiming / reclaiming in this way is still challenging to people.

One of the things that’s interesting about the “list” poster is that we chose multiple terms to identify ourselves. It was never, “I am a one thing,” it was always seven or eight different things, and three different versions of it because, on one hand there was no language with which to describe ourselves except for some derogatory language, or language that we claimed like, “amazon,” that was like putting ourselves out there. But there was also the desire not to be defined in one way or another. To be all these things. You can be all these things, you can be many things, and it isn’t static—it’s a spectrum. It’s why that poster still works— it’s inclusive.

Another consideration is the voice— who we are speaking to. “I am a _______ and proud,” “I am a _______ and so are you.” We turn the tables to address the first person— to you—the reader.

As for the “And So Are You” façade, at Leslie-Lohman, that came from earlier posters, where we used our baby pictures. We decided to re-look at those posters from the 1990s, and we decided to blow them up big, make them monumental. We also brought in new baby pictures of friends—widening the umbrella.

Anybody can relate to those baby pictures—everybody has a baby picture—and what’s been super interesting is the amalgam of people across age, gender, race—people see themselves. Or, they have something acknowledged that wasn’t ever acknowledged [before]. The whole façade is about taking that space—it becomes safe space, queer space, you know, we’ve made this space that people can come to, and feel part of, and politically and socially that’s really necessary right now.

With the baby pictures, too, what you’re called is so important especially as a young person but also as an adult. Your name, your pronoun, those things, what clothing you’re made to wear. That can be very damaging and painful for people. So these posters recognize that, these are little tender beings that are us, that are all of us. And people are finding themselves in those pictures.

Why did you decide to use lower-case letters for “fierce pussy”?

It’s non-hierarchical, for one thing.

It looks good on the page, it looks more open.

It makes enough of a statement… Some people can hardly say fierce pussy, if you put that in the subject line of your email it still gets flagged. You don’t need it to be flaring in caps and screaming, it does all its own work.

*This interview has been edited and condensed throughout.